During the Nordic World Ski Championships in Oslo this year, the crowds cheered every time an exhausted Marit Bjørgen stumbled across the finish line, winning yet another gold medal.

This contrasts sharply with the basis of Kerstin Bornholdt’s recent doctoral thesis in history, which was submitted to the University of Oslo.

The story begins with the Olympic Games in Amsterdam in 1928, when women were allowed for the first time to compete in the 800-metre race. Line Radke-Batschauer of Germany completed the race in 2:23.8, and became the world’s first Olympic champion in the 800 metre for women. However, not everyone liked what they saw: women who sweated, breathed heavily and threw themselves on the ground after crossing the finish line.

“Any doctor who saw how even experienced female athletes collapsed and were lying on the ground after the race could not support this kind of athletic competition for women,” wrote the German doctor H. Franzmeyer following the race.

The 800-metre race in Amsterdam was the start of a heated international debate about women, sports and health. The result was that the 800-metre for women was discontinued as an Olympic sport. It was not reinstated until 1960.

“The debate surrounding this 800-metre race sums up the issues I address in my doctoral thesis. The Olympic Games in 1928 were an international event that triggered similar reactions in many countries. You can see an interaction between the national and international debates that took place in the aftermath of the race. In addition, medical knowledge played an important role in the decision to discontinue the 800-metre race for women at the Olympic Games,” says Kerstin Bornholdt, whose thesis explores how medical knowledge about women and sports was developed in Norway, Denmark and Germany during the interwar period.

Medicine and ethics

“In the debate following the 800-metre race in Amsterdam, it appears that the doctors acted primarily as a roadblock to women in sports and that they used arguments that lie outside what we think of today as strictly medical knowledge. Is that right?”

“Some of their arguments were based entirely on ethics, but not all. During the interwar years, some doctors believed that it was harmful to sweat, breathe heavily, become exhausted or lose control over one’s body. They were concerned about this in the male athletes as well, but they were most worried about the women. It was probably also more shocking to see women sweat and exert themselves,” says Bornholdt.

In her doctoral research, she studied all of the major medical journals in Norway, Denmark and Germany, as well as the popular-scientific publications about medicine and sports in the three countries during the interwar period. She looked at how knowledge about women and sports is produced through the interaction of doctors, physiologists, coaches and athletes, and how knowledge and argumentation is transferred from country to country and article to article.

“I wanted to document the prevailing arguments and then show where these ideas came from. I looked at what they based their analyses on and how they interpreted the knowledge. Medical findings at the time were interpreted to mean that women could not run far and that in any case they should not run long distances in competitions.”

Different interpretations

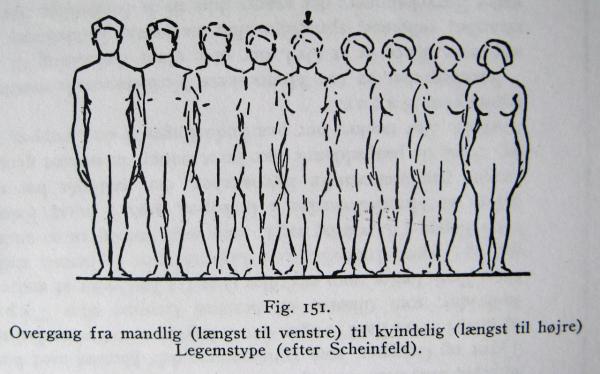

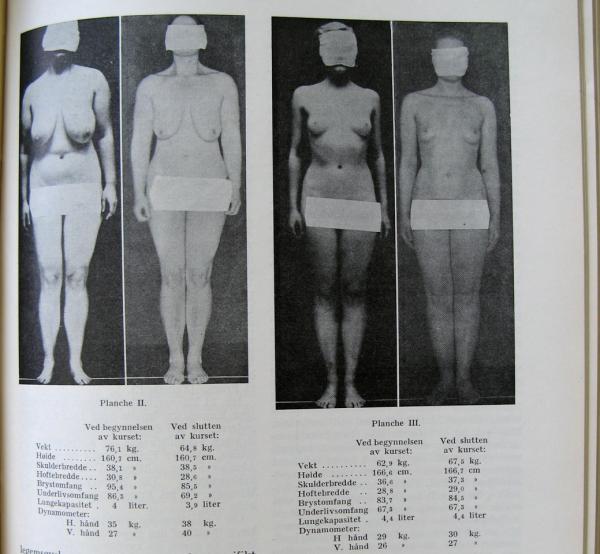

“For example, the doctors studied photographs of bodies before and after athletic training. The training resulted in female bodies that were broader in the shoulders and narrower across the hips, as these small changes were interpreted. Thin, muscular bodies were viewed as being typical of men. So one researcher wrote that it is the thin women who choose sports, then the next one interpreted this as it is the women with more masculine-like bodies who choose sports, and the next one wrote that sports leads to the masculinization of women,” Bornholdt explains.

The influential German gynaecologist Hugo Sellheim wrote articles claiming that female athletes have difficulty giving birth because of their narrow pelvises and that sports training could make them sterile. Fear of hermaphroditism also appeared in the research articles. Throughout the 1920s, however, some doctors changed their view of women and sports. Bornholdt points out that new medical knowledge was developed in the wake of the increasing numbers of women who began to participate in sports.

“Some doctors began to understand gender as something more complex. They stopped writing about female and male bodies in terms of a dichotomy, and wrote instead in terms of degrees and different types. Muscular female athletes represented a variation of the female body,” says Bornholdt.

Gymnastics

While women were entering the sports arenas and new knowledge about women and sports was being developed, new types of sports were coming onto the scene. The founders of these sports claimed that they were particularly suited to women. In Norway and Denmark, Björkstén gymnastics took over as the main sport for women. In Germany, many coaches and doctors believed that rhythmic gymnastics, a forerunner of today’s competitive rhythmic gymnastics, was the best kind of sport for women.

“Through analyses of female bodies that had undergone athletic training, doctors began to develop a more multifaceted picture of the female body. Gymnastics can be seen as an attempt to make everything more one-dimensional again,” says Bornholdt.

The basis for the Scandinavian women’s sport was the type of gymnastics developed by Pehr Henrik Ling of Sweden. Ling’s form of gymnastics was essentially gender neutral; both women and men took part. The participants would perform what the founder believed to be natural movements, in keeping with anatomical and physiological laws. During every gymnastics class, they would work with each individual body part, each muscle group and each organ. They would follow an instructor and move in step. The Finnish doctor Elli Björkstén introduced her gymnastics as a female variant of Ling’s gymnastics.

The objective of Bjørkstén’s exercises was new – the women would work on flexibility, elegance and lightness to develop good body posture. Bjørkstén’s variation caught on quickly. Doctors, coaches and others began to talk about what had been considered the gender-neutral Ling gymnastics as a male form of the sport. A striking example of this is the Danish gymnastics teacher Sigrid Nutzhorn, who in 1913 wrote a textbook on gymnastics for children in which she did not distinguish between boys and girls. In 1936, she had changed her opinion and published an article stating that Ling gymnastics was a masculine sport.

The German gymnastics

German rhythmic gymnastics was introduced in the 1920s. The pattern of movements was different than in Scandinavian women’s gymnastics, as it entailed a flow of one movement into the next. The ideal was movements in nature, the waves in the sea and the wind that rustled the tree tops. Rhythmic gymnastics has a lot in common with Rudolf Steiner’s eurythmy, which was developed during the same time period. Elegance was also a key objective in German women’s gymnastics. Interestingly, Scandinavian Björkstén enthusiasts thought that the German form of gymnastics was very unaesthetic. A Scandinavian supporter of Björkstén wrote that German women’s gymnastics reminded her of bodies writhing in pain and vomiting.

“It is very interesting to see how the doctors interpreted gymnastics. For instance, the researchers wrote that women have expressive muscles, muscles that are suited to making elegant movements,” says Bornholdt.

Physiologically speaking, there is no such thing as expressive muscles. There are, however, two types of muscle fibre – long and short. Athletes who have an abundance of long muscle fibre are better suited for long-distance and endurance sports, whereas those with more short muscle fibre have an especially good basis for participating in explosive sports such as sprints and broad jumping. All of this was common knowledge within the medical community during the interwar period.

“The researchers knew that there was no such thing as expressive muscles, but they wrote about it anyway. You can even find this in the same article. First the author asserts that there are two types of muscle fibre and a bit farther down in the same article comes an explanation about women’s expressive muscles. This shows an interesting encounter between science-based knowledge and popular notions, and especially how prevailing ideas affect knowledge production within the medical field,” says Bornholdt.

Translated by Connie Stultz.

Kerstin Bornholdt: Between Exhausting Sports and Swinging Rhythm: An Inquiry into Medical Knowledge Production about Women's Sports and Women´s Gymnastics in Norway, Denmark and Germany in the Interwar Years, submitted to the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo.